20 Low-Budget Films That Became Cult Classics

20 low-budget cult films that are actually masterpieces.

Long before I dove headfirst into the world of professional writing and academia, I lived the life of a true cinephile. My early undergraduate studies revolved around film theory and history, with a fair touch of low-budget indie production on the side.

Eventually, I even ran the media department for a small non-profit, plying my skills professionally. My trajectory in the professional realm may have shifted somewhat since those days, but my love of films remains as bright as ever.

With plenty of time indoors during the 2020 shelter-in-place orders, I found myself exploring some of my favorite cult classic films and marveling at what these production teams did with budgets that — by Hollywood standards — were barely worth the shells, never mind the whole peanuts.

I wanted to dive a little deeper into what went into creating these films and how those low budgets may have contributed to making them some of the most classic and beloved items in any cinephile’s collection.

What is a cult film?

The criteria for a “cult film” are not clearly defined across all boards, but a few basic elements remain consistent. The term “cult film” became commonplace through the 1970s and referred primarily to a specific type of low-budget, art-house, or otherwise “underground” (outside the mainstream in some way).

The term has become vaguer, however, and while it might still often refer to films that are somehow transgressive to the norms of the mainstream, it can also refer to films that have simply gained dedicated fan followings, or films that were suppressed or lost and have since been recovered and gained a renewed appreciation that way.

For this article, I concentrate on a mix of films. Some have a strong tie to some aspect of the term “cult film,” even though some have reached such a degree of cultural saturation that the term might feel stretched.

Others in this list are closer to true art-house pieces, films which, because of content and budget, never hit it big with the larger culture, but still managed to capture the unique zeitgeist of a specific point in time.

What counts as “low-budget”?

This is a question that confuses people time and time again, largely because the language of everyday life and the language of cinema production are not always synonymous.

In real-life terms, a million bucks is still a fairly sweet amount of cash for most people. For Hollywood, producing a film on a budget of a million dollars is like producing a run of Hamilton with nothing for the set but cardboard boxes and crayons.

Necessity, however, really is the mother of invention. The limitations posed by low budgets can force the production team to make smarter decisions, opting for clever choices instead of extravagant ones — and, in so doing, they often end up generating the sort of vibrant visual landscape that offers something unique to the world.

Another consideration when looking at the meaning of “low budget” is the nature of different film genres.

A family comedy or a crime drama can much more easily survive on a budget of just a few million, whereas a science fiction action film (famously the most expensive genre) is going to be hard-pressed to get by on less than 15–30 million.

Therefore, the topic is scaled somewhat depending on circumstance, but all of the films here will fall beneath a 30-million dollar budget, and most will come in far below it.

The Full Monty (1997)

Budget: $3.5 million

A film that turns the hardships of the real into a chance for joy, The Fully Monty delivers its promise, showing up in a way nobody expected.

Set in the remnants of the steel era, when the industry’s downfall took local economies and lives with it into the dregs, The Fully Monty manages to tackle several important themes, including classism, poverty, and homophobia, all while sweeping the viewer away with a heartfelt and sincere sense of hope in the face of all that can go wrong when the trends of the world leave the little people behind.

At once charming, funny, and (for its time) audacious, this little film packs a real punch.

Did you know?

With a budget of only $3.5 million, the film’s 250 million takeaway cements it as a true cinema success story.

Upon arriving on the screen, it took critics by storm, catapulting the film to the top of the charts on both sides of the Pond, to be finally eclipsed only by the science-fiction hit Contact by Carl Sagan and the powerhouse blockbuster Titanic. It continued to win awards even in the face of heavy competition from that year’s film lineup and spawned a number of stage adaptations which themselves received positive reviews.

Moon (2009)

Budget: $5 million

Moon hit the silver screen in 2009 to rave critical reviews. The indie film, completely shot in a studio for $5 million, managed to nearly double its budget in the box office at $9.8 million.

Filming a science fiction story, especially one which aims to maintain realism, is not an inexpensive task, but Duncan Jones went to great lengths to keep costs as low as possible (hence his decision to shoot entirely on a constructed set, where all elements of the production could be controlled).

Most of the effects of the film are practical, utilizing real models enhanced with digital animation to create the surface of Earth’s lonely satellite. The cast, likewise, remained small to ensure that the total cost could be further reduced — though the sparse script plays into this well.

Jones said that he wanted to create the sort of science fiction film that would appeal to a sci-fi literate audience, the sort of film that he would want to watch. He drew inspiration for his thematic touches from classic science fiction hits like Silent Running (1972) and Alien (1979), which were staples of Jones’ childhood.

Did you know?

A professor at NASA’s Space Center Houston requested that Moon be screened as part of a lecture series due to the film’s conceptual use of Helium-3 (an energy source that NASA has been exploring for space settlement and travel).

As it turned out, other elements of the film unintentionally anticipated other areas of real-world research, such as the use of Moon regolith mixed with water from the frozen lunar poles to create “mooncrete” to be used in permanent lunar structures.

My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002)

Budget: $5 million

It’s likely that you’ve seen, or at least heard, of this cult classic film. But did you know that it was made with a budget of just five million dollars? Knowing that, would you believe that it grossed 368.7 million in the box office?

My Big Fat Greek Wedding is a romance unlike any other, partly because of how sincere it feels. It captures its niche perfectly, never compromising itself for the good of Hollywood’s over-inflated sense of the importance of melodrama; its tensions feel at once real and charming, and the growth of the plot is a humorous exploration of how love and family systems intertwine.

Did you know?

My Big Fat Greek wedding began as a completely different sort of production. In 1997 Nia Vardalos, who stars in the film as Fotoula, wrote the original script as a one-woman play which ran for six weeks out of the Hudson Backstage Theatre in Los Angeles.

It managed to do well during its run, frequently selling out due to heavy promotion to Greek Orthodox church communities in the area. High-profile actors like Tom Hanks also saw it live, and the play soon garnered interest from producers and studio executives.

The film almost never materialized because producers wanted to make massive changes that Vardalos objected to (changing the ethnicity of the main family to Hispanic, for instance). Then, Tom Hanks’ own production company, Playtone, stepped in. After signing a film version that would maintain the integrity of her vision, they also agreed to produce a new stage version, which would this time take place at LA’s famous Globe Theatre.

I’ve always seen this as a huge reminder that producers don’t know what they need, only what they want (and what they want is usually not what they need).

It behooves creative-types trying to get their work out there to stick to their values and avoid caving in to pressure from those whose only interest is financial (especially because there’s no predicting what will become one of the biggest financial success stories of the decade).

Get Out (2017)

Budget: $4.5 million

Under the surface of the people in your life, what really thrives? What rivers run in the sub-currents of the mind?

Exploring the concept of racism in the United States is not new for filmmakers, but Get Out managed to bring it to light in a way that captivated audiences, and at just the right time for it to explode on the critical and financial stage.

Though made with a budget of just $4.5 million, the film topped out at $255.4 million in the box office, unequivocally turning it into one of the great indie-film success stories of the last century.

The film’s dealing with racial concepts was lauded by critics worldwide, and its horror-motifs were praised for both how emotionally-intense they were, and for how they served the film’s meta-purpose of uncovering structural racism beyond traditional tropes.

Did you know?

There were other endings considered for the film than the one which audiences ultimately saw.

Peele wanted to illustrate the pervasive and ingrained issues with racism, but finding just the right way to tie things up proved difficult. Real-world awareness that rose up during the mid-2010s regarding police brutality, however, led Peele to pick the ending that he did, believing that it suited a more “woke” audience.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975)

Budget: $400 thousand

The Monty Python group was ready to break out of the television world and try something new on for size.

The result turned out to be one of the funniest cult films around, its memorable and quotable moments stacked up on a zany pile of random humor and classic Python gags.

This film always felt like a grab-bag of jokes to me, with some sticking and some falling straightaway to the floor — but, in true Python fashion, sometimes the gags that fall flat are the funniest of the lot.

Detailing a comic vision of the Grail Quest from Arthurian legend, The Holy Grail is a madcap reenactment of a number of iconic Arthurian tales woven together with a wide range of gags, twists, and semi-connected skit-scenes that tangentially move the whole plot forward toward its uncertain end.

Did you know?

One of the many iconic elements of the Holy Grail is the use of coconuts clapped together by members of the on-screen cast, in combination with a prancing hop utilized by the actors playing knights on horseback to mime the experience of riders on horses.

This, however, did not exist as an original intent of the Pythons who had planned for there to be horses in the film.

However, when it became clear that the film’s meager budget precluded the hiring of horses (save for a lone horse visible in some scenes), the crew came up with the idea of using the coconuts instead. This is a direct reference to classic radio-programs where coconut halves clapped together provided listeners with the audio effect of horses’ hooves.

The film managed to gain an initial budget of just $200,000 by reaching out to ten private investors for $20,000 each. Most notably, these investors included the legendary rock bands Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and Genesis (which Terry Gilliam ascribed to the rock bands’ willingness to take advantage of UK tax laws at the time by financing the British film). With the film’s final budget barely breaking $400,000, its box office result of $5 million certainly makes it a financial success story.

The Holy Grail did fairly well during its initial release, critically, though reviews were generally mixed. It gained an increasingly-powerful cult following in successive years, however, and now sits cemented firmly as one of the great cult classics. Decades later, Eric Idle would use the film as the basis for the hit-musical Spamalot.

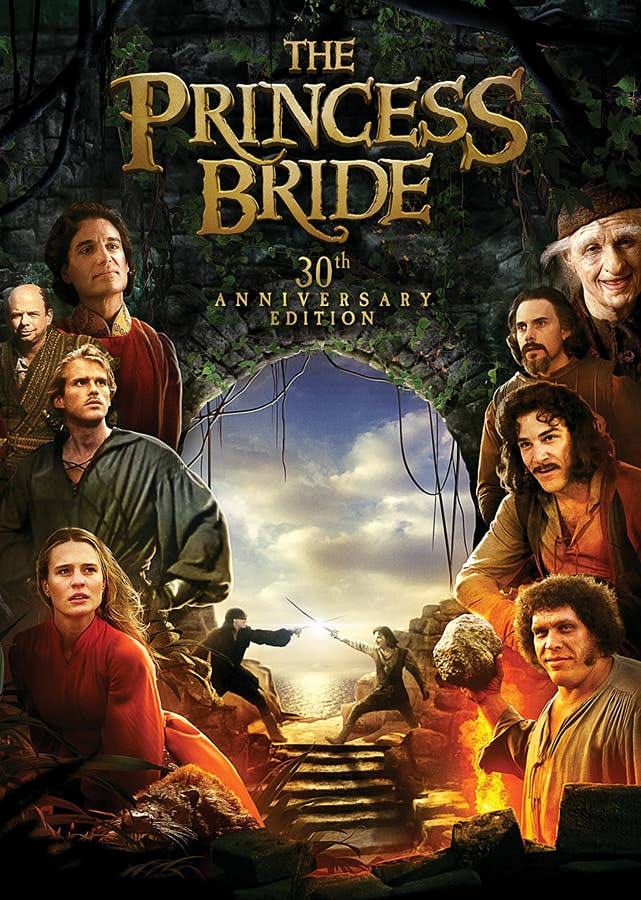

The Princess Bride (1987)

Budget: $16 million

“As you wish” became the most powerful romantic phrase after the Princess Bride hit the silver screen, its smoky delivery by actor Cary Elwes capturing the hearts and imaginations of everyone who saw it. Based on the book of the same name, the film treats the viewer to a wacky wonderland of daring-do, adventure, high-villainy, and sweet romance.

The premise involves a kidnapped princess, a stableboy-turned-pirate, a giant from Greenland, a short, medieval, Sicilian mobster, and a Spanish fencing master intent on fulfilling his revenge against the mysterious six-fingered man who killed his father — none of which are the weirdest or wackiest moment in the story.

This is an example of a film with such a powerful cult status that the cult has very nearly eclipsed the film; the phrase “My name is Inigo Montoya, you killed my father, prepare to die” is likely recognizable even to people who have never come close to watching the film, and the very name “The Princess Bride” seems to have filtered into the everyday background knowledge of even the least-film savvy of people.

It’s a personal favorite of mine, partly because it transcends the concept of a film that “needs to be serious” while maintaining some of the most emotionally-charged moments of high drama I’ve ever seen, as well as for the wacky aesthetic and the flashing sword fights. The Princess Bride manages to never go exactly where you expect it to, while always leading you to the next moment of revelation, danger, and excitement.

Did you know?

There are honestly too many wonderful anecdotes about this film to list them all here, but I’ll go with a few of my favorites. The first is potentially the most devastating: The Princess Bride almost never got made!

Before director Rob Reiner turned the story into the classic film we all know and love, a number of studios had already tried and failed to bring the whimsical tale to life. 20th Century Fox even purchased it for $500,000 but, after failing to do anything with it (due to a change in the leadership of Fox) William Goldsmith bought back the rights with his own money. Even iconic directors like François Truffaut and Robert Redford had tried to take charge of the project and turn the film into a reality, only to see fate intervene time and time again.

Reiner who loved the story ever since his father gave him a copy of Goldsmith’s original book, hung on like a terrier, however. Despite being told that “it couldn’t be made” he fought for it and managed to leverage the financial support of his friend Normal Lear (the famous television writer) into a new deal with 20th Century Fox that would see the film distributed once made.

Since then, Reiner remained a steadfast supporter of the film and the story, organizing events and participating in fan-made projects based on the work. During the filming of the original film, he invited the cast over to a house he rented nearby for frequent dinners, which many believed helped to foster a sense of family between the cast.

In 2020, a fan-made version of the film actually starred both Rob Reiner and his father Carl Reiner (himself a noted actor and writer). Rob Reiner played the “grandson” to whom the grandfather (played in this film by Carl) reads the story of The Princess Bride. This would be Carl Reiner’s final performance, as he passed away a few days later due to a fall at the age of ninety-eight.

Though Princess Bride never made a massive box-office success, its cult following is undeniable, and it did manage to double its budget by the time the worldwide box office numbers were in. Regardless of the financial side of things, this is one film that forever changed the way comedy films were approached on the big screen.

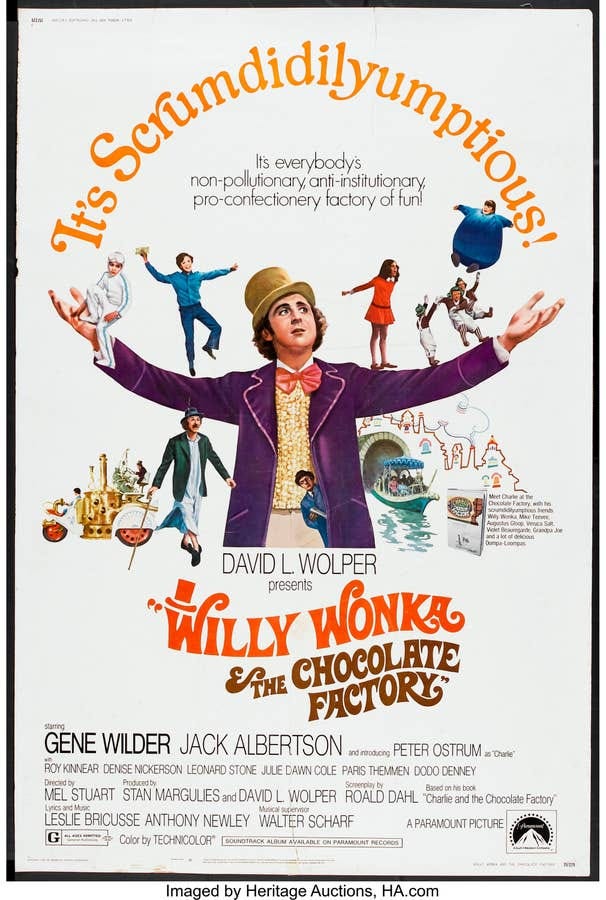

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971)

Budget: $3 million

It makes perfect sense to me that in 2014, the Library of Congress decided to preserve Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory in the United States National Film Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

It certainly gained the sort of cult following through the decades that never seemed to quit, spilling over into the public consciousness to such a degree that almost anyone will recognize the title even if they’ve never seen the film.

I loved it as a kid and I continue to love it as an adult, especially because Gene Wilder’s performance produces such a sense of enigmatic flare to every scene that it captures and thrills the senses.

It may not have been the film that Roald Dahl — the author of the original book upon which the film was based (Charlie and the Chocolate Factory) — wanted to see made, but it managed to become a powerful work in its own right, formed of just the right stuff to capture the imaginations of decades of viewers.

The film ultimately succeeded in the box office, but only barely, taking $4.5 million against its small budget of $3 million dollars.

Did you know?

Not only did Dahl not like the film, he actively disowned it, despite having written the original script. He disagreed with casting and directing choices, but especially disagreed with changes made to the script that the producers felt would be necessary to make it more palatable to audiences and especially children (these included the addition of a villainous character, to which Dahl vehemently disagreed).

Gene Wilder also accepted the role of Willy Wonka on one very specific condition: the specific nature and design of his introductory scene.

“When I make my first entrance, I’d like to come out of the door carrying a cane and then walk toward the crowd with a limp. After the crowd sees Willy Wonka is a cripple, they all whisper to themselves and then become deathly quiet. As I walk toward them, my cane sinks into one of the cobblestones I’m walking on and stands straight up, by itself; but I keep on walking until I realize that I no longer have my cane. I start to fall forward, and just before I hit the ground, I do a beautiful forward somersault and bounce back up, to great applause.” — Gene Wilder

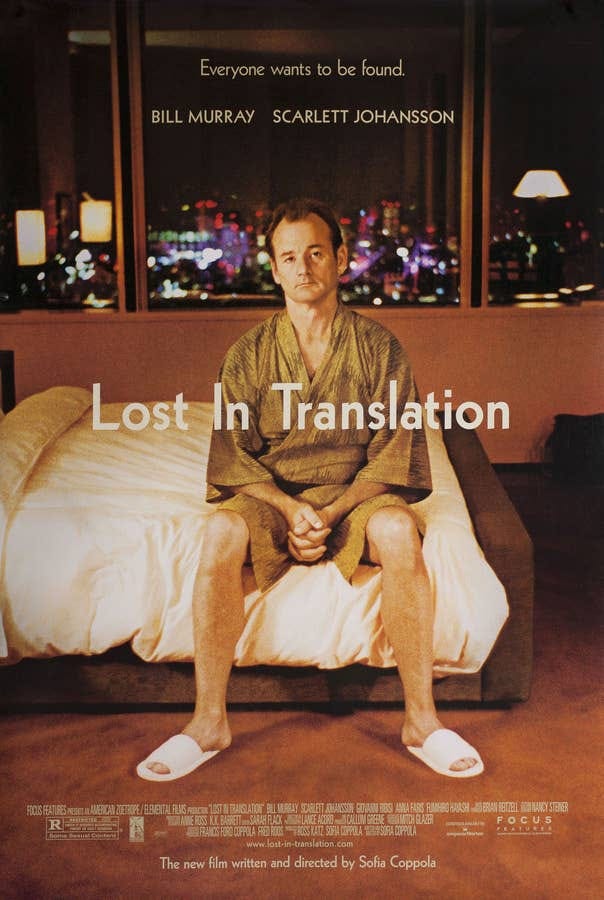

Lost in Translation (2003)

Budget: $4 million

Starring Bill Murray and Scarlet Johansson, Lost in Translation was emergent director Sophia Coppola’s first major film break.

With an initial budget of just $4 million, the film would go on to confound all expectations, breaking $118.7 million worldwide.

The film proved Coppola’s ability to capture a powerful aesthetic experience on the silver screen, as well as her ability to draw up new associations from commonplace themes, presenting an otherwise simple storyline of midlife crisis and alienation, in a way that refused to play into known romance-genre tropes.

Did you know?

Bill Murray never officially signed a contract after agreeing to Coppola’s request that he take on the lead role in her film.

She would continue to prepare for the film, raising money (including her own funds) in order to prepare for production, all without knowing if Murray would even arrive on set. When he did, mere days before filming was set to begin, Coppola described a feeling of significant relief.

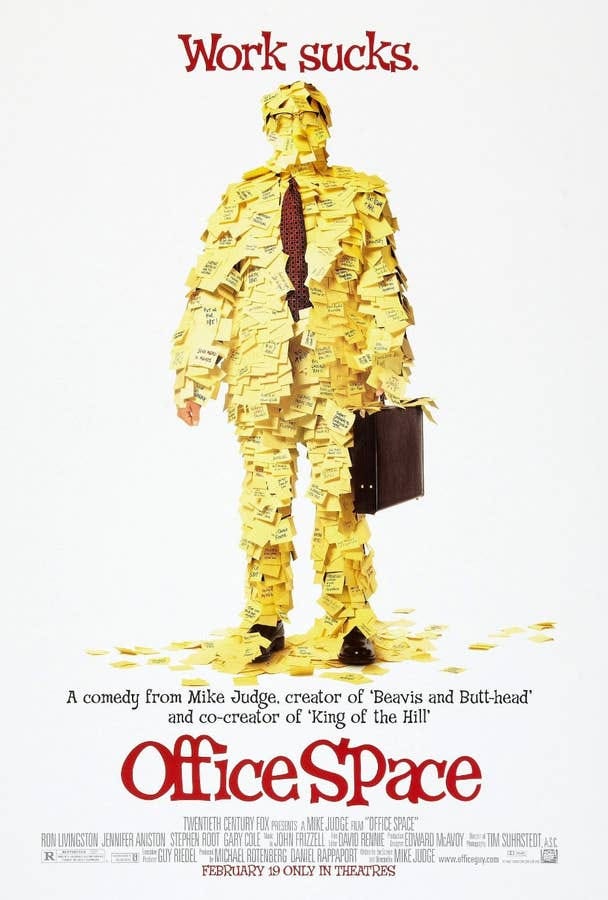

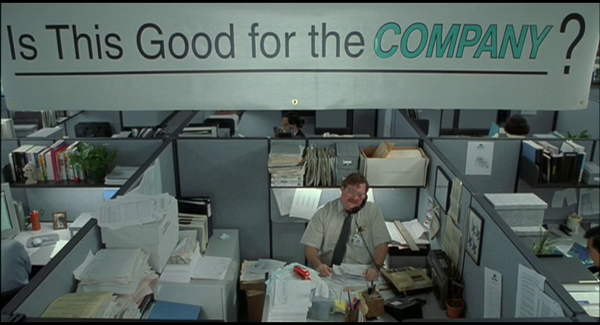

Office Space (1999)

Budget: $10 million

Office Space is a great example of a film that did not go quietly into that good night, despite its financial failure in the box office and general mishandling by the studio and executives who handled its promotion.

Though it barely made more than its 10 million dollar budget with 12.2 million, it gained an avid cult following after its release to home video and remains a popular cult film from the era today.

Lampooning the “white collar” office worker grind common within information technology companies at the end of the 20th century, Office Space is a sly film with the sort of humor that always dances just at the edge between quiet and garish.

Moments where the humor takes a long time to build, or slips and misses its target, are buoyed up by the heist-plot that carries the action and the various excellent performances that the cast displays.

Did you know?

When preparing to film Office Space, the crew tried contacting two different stapler manufacturers for permission to use their stapler in the film.

After both declined, Swingline offered the use of their stapler, and, after the film popularized a red version (which the crew created by using spray paint on an uncolored stapler), Swingline released a line of polished red staplers to support demand from fans of the film. Stephen Root, who played Milton in the film, has said that now, whenever he arrives on a new set, the crew usually has a box of red Swingline staplers awaiting him.

The creation of a special line of staplers is not the film’s direct cultural impact. In the film, the prescription at TGI Friday’s restaurants that their employees wear “flair” in the form of various pins or declamatory buttons was satirized heavily, and formed the primary plot arc around Jennifer Aniston’s character was built.

Afterward, TGI Fridays dropped the “flair” requirement, with the cult success of the film widely being labeled as the reason.

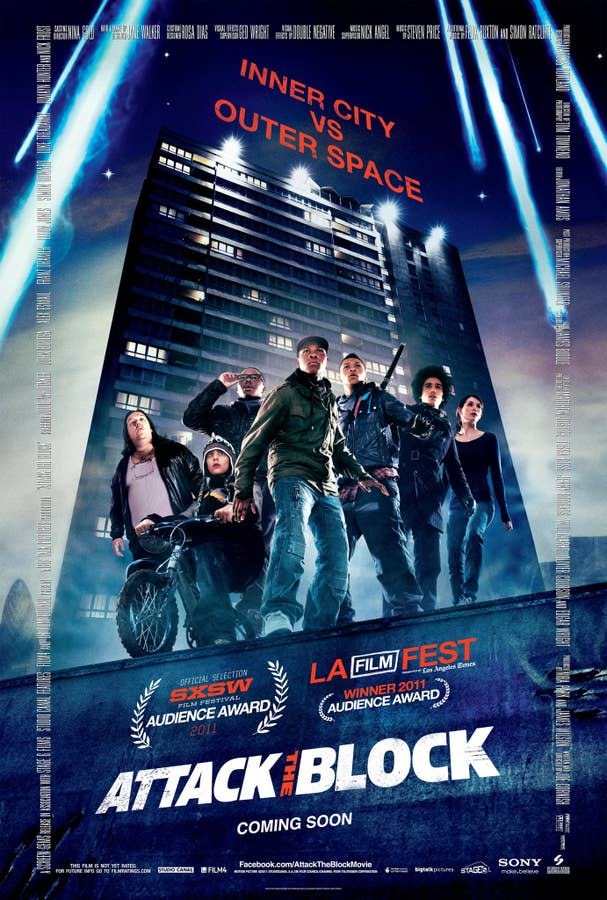

Attack the Block (2011)

Budget: $11 million

Science fiction stories are typically known for their ability to examine and dissect social issues taking place during the time of their creation, and Attack the Block follows this trend swimmingly. The director and writer, Joe Cornish, specifically wrote the script in order to counteract films where young urban hoodlums were depicted only in the worst light.

The main source of confrontation in the film is between a group of aliens who have landed in urban London in the dead of night and a gang of local teenagers who make a living by committing petty crimes.

As the tension of the plot escalates and the action forces the story along, the characters’ lives are slowly revealed in greater detail, providing the audience with a chance to empathize and connect, regardless of how different the youths might be.

I loved the way the story drew upon classic science fiction tropes while still managing to produce something fresh, largely through the aforementioned character-work.

The special effects for the film were also superb. Despite being a raving critical success, however, the film did relatively poorly in the box office, taking just £4.1 million pounds (around $5.7 million dollars) after an £8 million pound budget.

It became a cult star, however, one which would catapult the careers of both John Boyega and Jodie Whittaker, who would later become the stars of major science fiction franchises Star Wars and Doctor Who, respectively.

Did you know?

Most of the teenagers who starred in the film were drawn directly from urban drama programs in the same area as the fictional setting of the film. Cornish wanted to capture an authentic experience of life in these areas and wanted his actors to fit the characters naturally.

The Multicultural London English spoken by such characters throughout the film highlights this.

Under the Skin (2013)

Budget: $13.3 million

Telling the tale of a mysterious woman who hunts men throughout the cities and wilderness of Scotland, Under the Skin captures a darkly beautiful otherworld aesthetic that few films of the 21st century have managed to match.

Included both on lists of the best films ever made, and those of great films that bombed in the box office, Under the Skin is a visually stunning film that manages to twist old sci-fi tropes into an artistic powerhouse.

It only made $7.3 million on a $13.3 million dollar budget, despite its positive reception.

I remember watching this for the first time just after it came out in my film theory class and finding myself surprised at how few of my fellow film students seemed to appreciate the subtleties that the film reveled in.

Critics generally agreed with my perception of Under the Skin, however, including in Cahiers du Cinéma, one of the most influential film magazines in the world (where Under the Skin ranked third on their chart of the top ten films of 2014.

Did you know?

The film utilized custom-designed hidden cameras for the scenes where the men are being picked up by the main character in her van. The men were actually real random people who were only informed that they had been filmed after the fact.

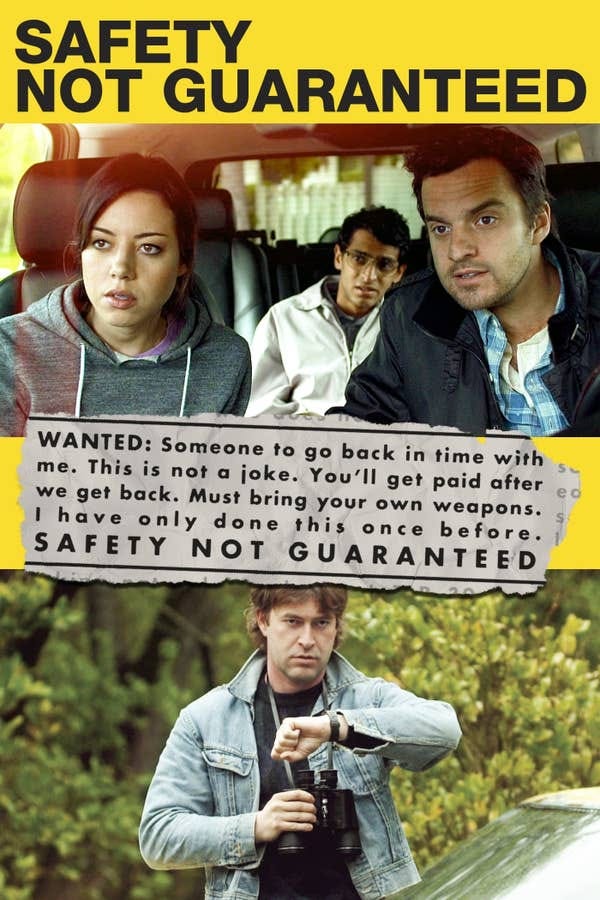

Safety Not Guaranteed (2012)

Budget: $750 thousand

It all starts with an ad in a newspaper.

Wanted: Somebody to go back in time with me. This is not a joke. P.O. Box 91 Ocean View, WA 99393. You’ll get paid after we get back. Must bring your own weapons. I have only done this once before. SAFETY NOT GUARANTEED.

I love this film partly because it manages to weave a compelling mystery in such a way that the viewer is constantly forced to re-orientate themselves and their perception of the film’s intent.

Besides, Aubry Plaza pulls off her signature disaffected acting style with ease, playing her part perfectly across from actor Jake Johnson.

Did you know?

The film actually got rewritten with Aubry Plaza specifically in mind, after writer Derek Connolly saw her performance in the film Funny People.

The whole film stems from an advertisement placed in a 1997 issue of the magazine Backwoods Home by Senior Editor John Silveira.

The advertisement was satirical but Connolly, who encountered references to it in 2007, did not at first know that its origins were farcical and would go on to remark that it made him feel really sad to think about someone who desperately wanted to go back in time, perhaps to fix something from their past, and this proved to be the fomenting force behind his initial script.

The film’s whole budget capped out at $750,000 while it went on to garner $4.4 million in the box office.

Given that this excellent success for such a small film, with a first-time director at the helm (Colin Trevorrow, the director, would follow this up by landing the director seat for the 2015 film Jurassic World), it’s no wonder that some have pointed to Safety Not Guaranteed as one of the films which proved to the world (and up-and-coming media giants like Netflix) that low-budget films could be breakaway hits, allowing for a whole new layer of possible productions to arise from scripts passed over by larger studios.

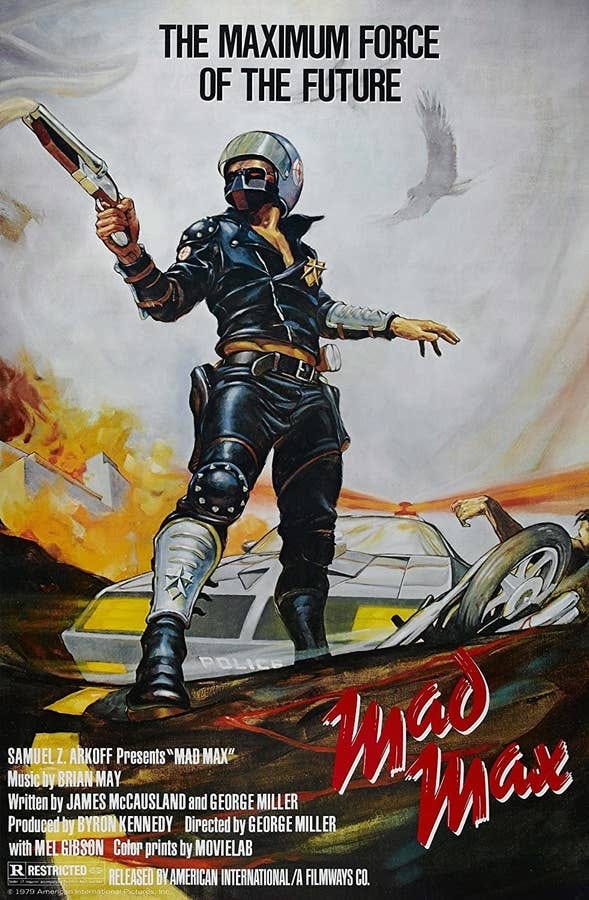

Mad Max (1979)

Budget: $400 thousand

Not as well known to the general public as its later siblings, The Road Warrior (Mad Max 2 in Australia), and Mad Max: Fury Road, Mad Max is the foundation upon which these later films were designed.

It also forms the backstory for the “Mad” Max encountered later in the series, with the events of this film building a platform for his journeys across the post-apocalyptic Wasteland.

The film is notable for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the casting of a young Mel Gibson in a role that would see him catapulted to international stardom.

Made for a budget of under $400,000, the film broke all the box office records with a box office take of one-hundred million, quite the surplus win for a novice director, screenwriter, and cast.

George and I wrote the [Mad Max] script based on the thesis that people would do almost anything to keep vehicles moving and the assumption that nations would not consider the huge costs of providing infrastructure for alternative energy until it was too late. — James McCausland, writing on peak oil in The Courier-Mail, 2006

Mad Max is ultimately a visceral action flick, hyper-focused on scenes of violence and mayhem, but its political undertones cannot be ignored.

Power dynamics are a feature in this film just as much as they are in the later installments, with the then-metaphor of limited oil as a background catalyst for the story feeling increasingly prescient in the era of climate-change awareness.

Did you know?

The original United States release of the film featured dubbed lines for almost every character because the purchasing studio worried that audiences would become confused by the frequent use of Australian slang and nomenclature throughout the script.

In terms of its critical acceptance, Mad Max received mixed praise and severe condemnation.

Some reviewers either appreciating it primarily for specific characteristics of the film, such as sound editing (and the film won awards in a number of such categories), while others felt that the film was “ugly and incoherent” with all the emotional appeal of “Mein Kampf.”

Stephen King, the grandmaster of horror himself, described the film as a “turkey.”

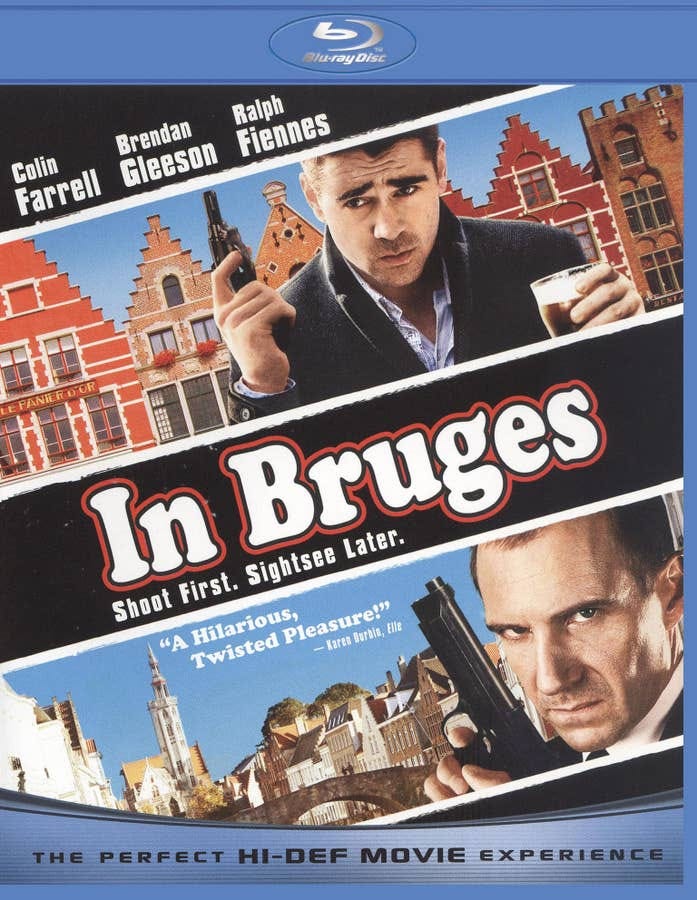

In Bruges (2008)

Budget: $15 million

This film always made it to the top of my favorites within the dark comedy genre, and considering its small but loyal cult following I’m clearly not alone.

The film actually did quite well in theaters and had one of the larger budgets of any of the films on the list, with $15 million. It grossed $34.5 million in the box office. Critics generally reviewed the film as favorable, and it received a number of awards.

Ultimately, however, the film slipped beneath the international radar, becoming a little-known star-studded indie production.

Constantly wringing acerbic humor from a very dark fabric, the film’s writing is undeniably intelligent and provoking, while its themes gave the actors room to maneuver and play.

Personally, I’d say that it’s part of a unique subset of dark films which try to blend gloom and “feel-good” moments together in a philosophic web — where others have failed in this goal, In Bruges manages to brilliantly succeed.

Did you know?

In Bruges features five actors who appeared in various roles within the extended Harry Potter franchise, four of whom were featured in the original film series.

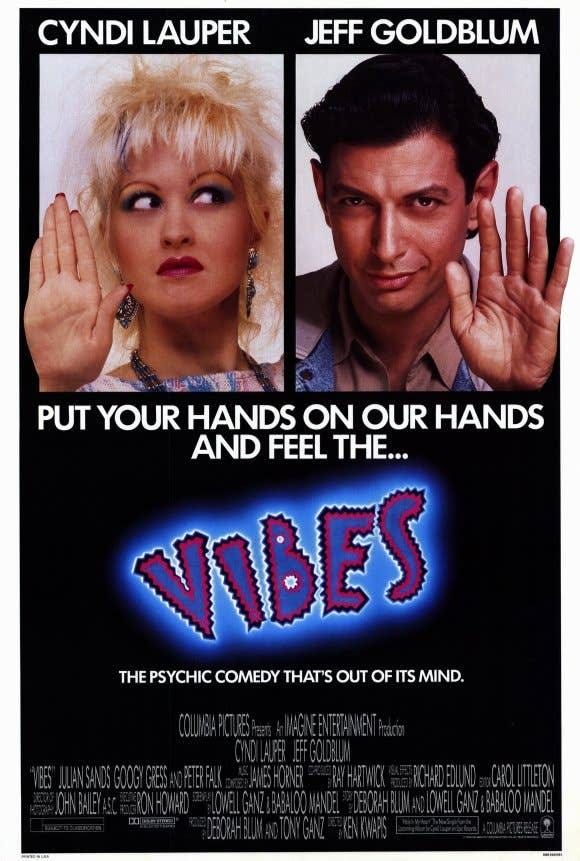

Vibes (1988)

Budget: $18 million

Imagine if there were a film starring Jeff Goldblum and Cindy Lauper about two psychics who go hunting for ancient Inca treasure and end up saving the world. Imagine such a thing right now.

Now, stop imagining it and go watch it because it was made back in 1988, and it is an absolute treasure.

The film crash-landed in a fiery ball of flame when it hit the box office, turning out less than two-million (compared to its 18-million budget). Critics, including film legend Roger Ebert, and for many it then drifted into that no-mans-land where law the bones of forgotten films.

The trick is, certain films are not made for the age that they appear in. Vibes is a quintessential 1980s film and, as such, it could never have succeeded in its own era.

Now, looking back at it, the way it captures the 80s through a delightful sense of parody fits the modern zeitgeist like a glove. The premise (originally pitched as “Romancing the Ghostbusters in the temple of Doom”) is campy and corny and just the right amount of weird, and the acting by the entire cast is filled with the sort of vibrant energy that can only come from actors who are having fun at their jobs.

Did you know?

The production studio originally tapped Dan Aykroyd to star across from Lauper, but the famous comedic actor declined after meeting Lauper and getting a closer look at the film.

While the immediate flop of the film probably made this a good choice for him, it also helped provide the film with the star it actually needed: Goldblum’s lanky sexiness and incredible eyebrows were the perfect complements to Lauper’s over-the-top caricature of an 80s gal trying too hard to be trendy.

Their magnetic charisma is a huge part of what makes Vibes so fun to watch, and thereby ripen with the passage of time.

Monsters (2010)

Budget: $500 thousand

There’s a technique some writers of the fantastic used where they drop a “normal idea” and a “crazy idea” side by side and turn them into a plot.

In Monsters, the normal idea is that there are alien monsters on Earth, taking up a good portion of the South American jungles. The crazy idea is that nobody finds this particularly crazy anymore — it’s actually quite normal to see a giant dead sea-monster washed up on a beach.

I remember being struck, the first time I saw Monsters, by how beautiful the moments of the film were. The landscapes are evoked in such a way that they become a character in their own right.

It also felt good to have a monster-sci-fi film where the menace remained primarily unseen; the looming shadow of suspense-filled every shot.

For a film produced across multiple countries on a budget of under $500,000, it managed to carry itself boldly, offering something fresh to a genre over-saturated by big studio blockbusters.

It managed to make $4.24 million in the box office, too, guaranteeing it a large enough audience to be considered a commercial as well as critical success.

Did you know?

The extras in the film were almost all untrained (and unpaid) extras, whose dialog and responses were all improvised on the spot.

Most of these people just happened to be in the area on the same day that the crew was shooting the film, and they were convinced to become immortalized on a pure volunteer basis.

The filmmakers also bucked convention by filming in a number of locations without permission, taking the concept of “guerrilla film-making” to a different level.

Garden State (2004)

Budget: $2.5 million

When Zach Braff wrote Garden State, he used it as an outlet for all the depression, loneliness, and frustration he felt at the time.

What emerged from that darkness turned on the lights for countless people around the world, doing what art does best: creating connections between human beings. Braff, longing for a “place that didn’t even exist” managed to pen a script that turned the darkness on its edge, providing the viewer with a meta-level experience that both captured the tragedy of life as well as the joy.

The cast, with Braff and Natalie Portman in the lead roles, played their roles to the hilt, providing the sort of committed approach to the bizarre landscape of the film’s plot and themes that help make Garden State such a success.

It’s a film about returning home, about grief, and about finding moments of joy in the middle of the hard times (as opposed to overcoming them completely).

Did you know?

The film’s hit status came about completely because of word-of-mouth efforts by Braff and the studio that purchased it. The film got made on a budget of only 2.5 million but it ultimately managed to net 35.8 million dollars at the box office, a solid financial win as well as an artistic one.

Braff toured for the film himself and helped to raise so much awareness of it that people were being turned away from the theaters that showed it due to a lack of seating.

Garden State has gone on to become a favorite with both the quirky cult crowd and a large portion of the mainstream in successive years, earning itself a fair bit of name-recognition outside the film-savvy crowd.

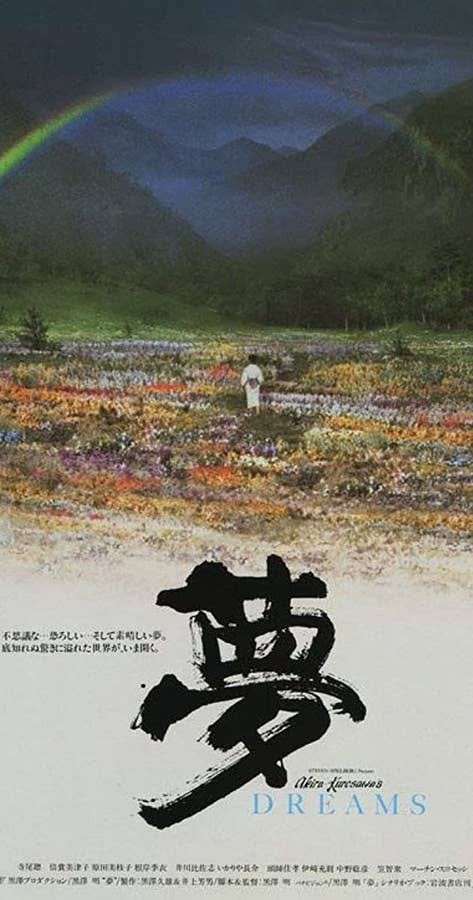

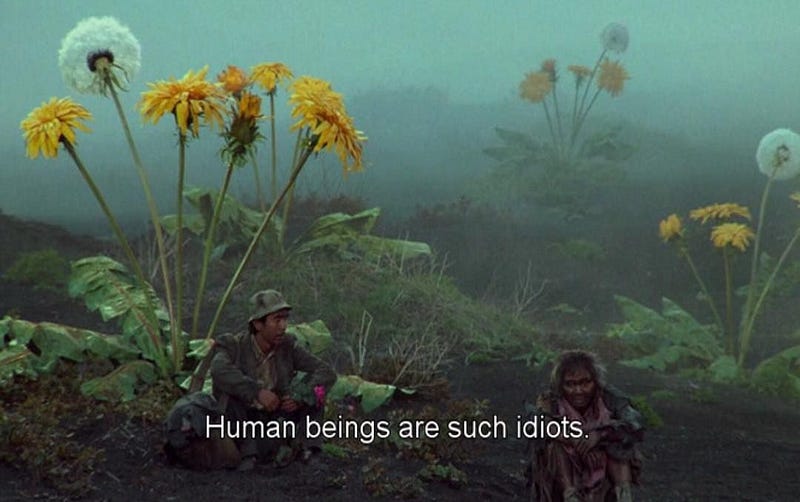

Dreams (1990)

Budget: $12 million

There are few filmmakers regarded with as much respect as Akira Kurosawa, the Japanese filmmaker whose work captured the imagination of other great film auteurs of the 20th century, including Federico Fellini, Martin Scorsese, and George Lucas (who took much inspiration from Kurosawa’s work when constructing thematic elements of Star Wars (1977).

It is, therefore, no surprise that Dreams, which Kurosawa said were inspired by his actual dreams, became a critical and cult success — even though it failed to make a dent in the less-than film literate general population.

Through eight different dream sequences, a surrogate Kurosawa explores concepts of religion, art, death, and the danger of human disregard for the natural world.

Each sequence is a brilliant cinematic tableau of magical realism, bursting with the sort of visual depth that only the very best film masterpieces manage to provide. Its artistry failed to capture the box office, however, and it gained only $2 million back against its $12 million dollar budget.

Did you know?

The special effects in the episode “Crows” were provided by George Lucas’s Industrial Light & Magic. Lucas, deeply admiring Kurosawa’s work, had already worked to produce Kurosawa’s international version of the film Kagemusha (1980).

The director Martin Scorsese also played Vincent van Gogh in the “Crows” sequence.

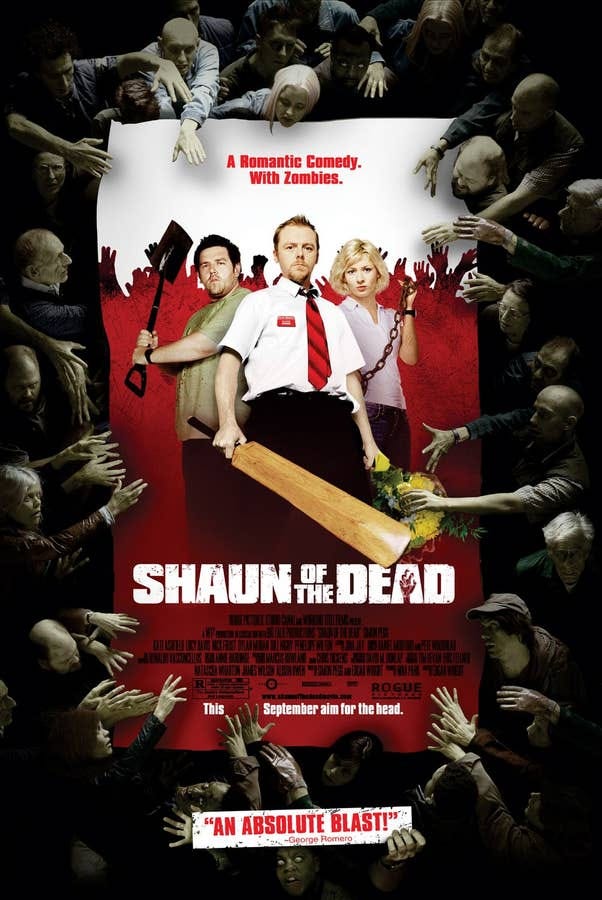

Shaun of the Dead (2004)

Budget: $6 million

Shaun of the Dead managed to revitalize the zombie genre in a way that challenged impressions of what could be done with such films.

Scripted by Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg, and based in part off of ideas that they played with during an episode of their cult-hit series SPACED, the film pays more attention to the foibles of the main characters than to the zombie hoard.

By placing emphasis more on the characters’ experience of the world and their relationships with each other, Shaun does a marvelous job of making the zombies nearly a background inconvenience to the lives of the characters, as well as a vehicle to the titular character’s rise to self-actualization.

Shaun of the Dead made $30 million in the box office on a $6.1 budget, instantly claiming financial success.

It also gained critical acclaim for redefining the genre, for the comedic timing, and for various aspects of the production from the score to the actors’ performances.

Did you know?

Originally, the film’s budget only allowed for a total of 40 zombies, to be played by professional stunt actors.

In a call-out to the SPACED fan community, however, Wright encountered massive support, and so many volunteer zombies turned up that “zombie auditions” needed to be held.

Further, when filming, local children gathered in such great numbers and with such zeal, that some 50 of them were selected for inclusion as child-zombies in the film.

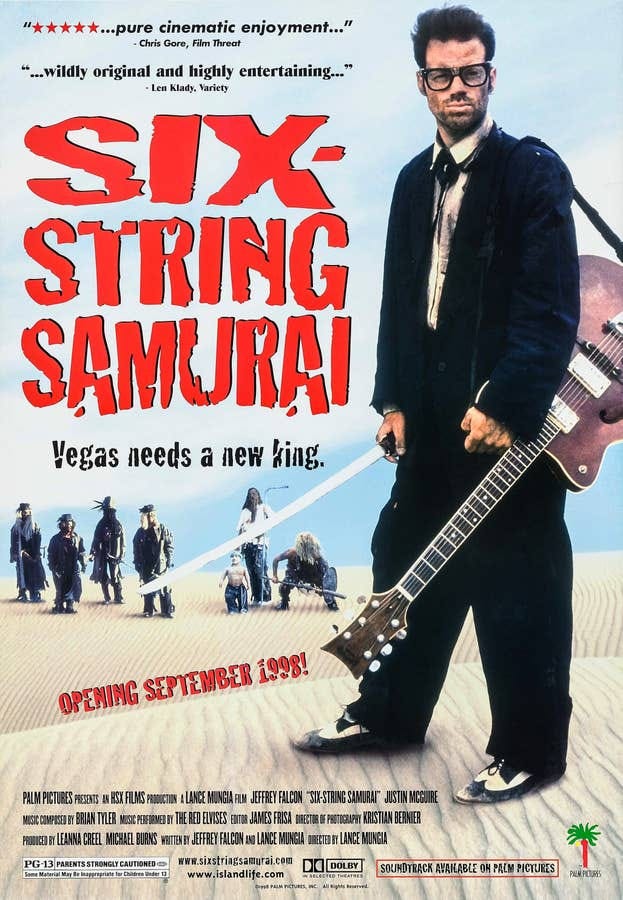

Six-String Samurai (1998)

Budget: $2 million

Throughout the entirety of Six-String Samurai, the vibrant notes of an electric guitar almost never cease, their hum permeating every instant of stylized visual, punching home the wonderfully bizarre world of the post-apocalyptic wasteland.

Though Six-String Samurai arrived in festivals to critical acclaim, it proved too offbeat for larger audiences, managing to take in only $124,494, not even a quarter of the film’s $2 million dollar budget.

Its unique homage to classic martial arts films and classic rock n’ roll, as well as its zany and satirical take on wasteland films (a favorite of the low-budget film crowd for obvious reasons), kept it flourishing as a cult film, however.

Though neither its director nor its lead star went on to have large film careers, Six-String Samurai cemented itself in a very specific niche.

Did you know?

Original plans for the film to be the first in a trilogy never panned out. However, 90s comic book legend Rob Liefeld (co-creator of Deadpool), took on the task of continuing the story, co-writing a graphic novel continuation that his own company produced.

Through this and other pop-culture references (like the inclusion of a reference to it in the video game Fallout), Six-String Samurai remains alive and kicking… just like rock n’ roll.